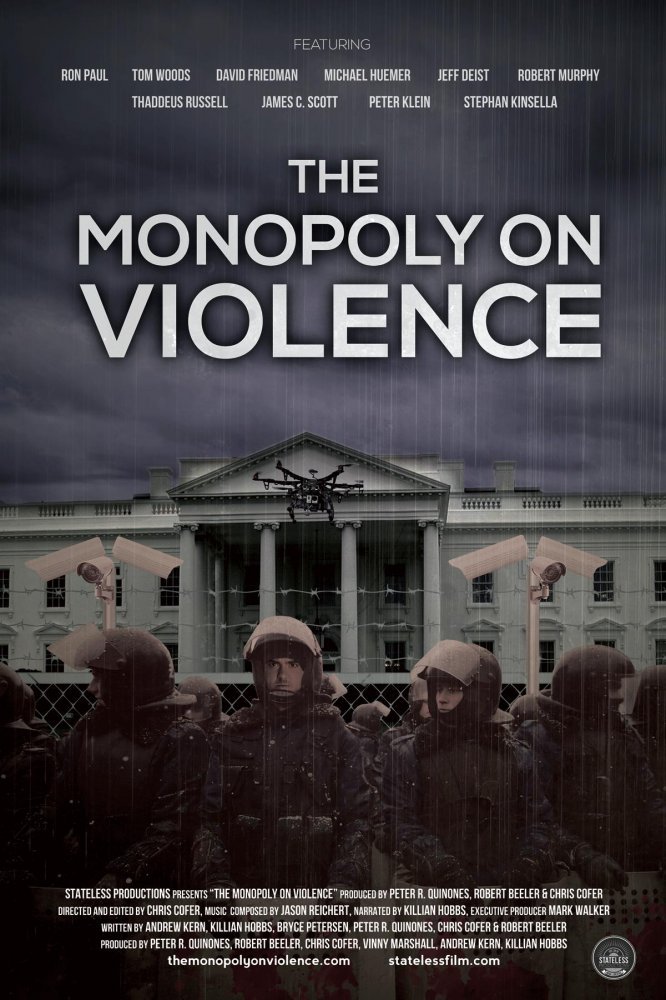

In the realm of political theory and practical governance, few concepts are as simultaneously foundational and contentious as the principle that states must have a monopoly on violence. This principle posits that for a society to achieve stable governance, its state must be the sole entity with the authority to use or sanction the use of physical force. This concept is not only a cornerstone of modern nation-states but also serves as a lens through which we can examine historical contexts, such as various armed factions within early Israeli history, and contemporary debates, notably those surrounding American gun rights.

The origins of this principle can be traced back to Enlightenment thinkers who sought to understand the nature and purpose of government. At its core, the idea suggests that by surrendering some degree of personal freedom—specifically, the freedom to exercise violence—the individual gains protection under an organized societal structure. This trade-off forms part of what is known as the social contract: citizens agree to abide by certain rules and norms in exchange for security provided by the state.

In examining early Israeli history, we see a fascinating case study where multiple groups vied for power in shaping a new state’s identity and governance structures. Armed factions such as Haganah, Irgun, and Lehi played pivotal roles during this formative period. Their eventual integration into or disbandment by Israel’s official military forces illustrates how emerging states wrestle with consolidating violent capabilities under centralized control—a necessary step toward achieving recognized sovereignty and internal stability.

Fast forward to contemporary America: discussions around gun rights vividly illustrate ongoing tensions related to this monopoly on violence. The Second Amendment has been interpreted by many as enshrining an individual’s right to bear arms—a provision unique among advanced democracies—which complicates efforts at centralizing violent capacity strictly within governmental institutions like police forces or military branches.

Critics argue that widespread private gun ownership challenges the state’s ability to maintain public order effectively; proponents counter that it represents a vital check against potential governmental tyranny—an insurance policy preserving liberty. Herein lies one of democracy’s great paradoxes: balancing individual freedoms with collective security.

Navigating these waters requires nuanced understanding rather than binary thinking. On one hand, unchecked private arsenals could undermine rule-of-law principles critical for civic trust and cooperation; on another hand, overly aggressive disarmament efforts might erode foundational liberties perceived as essential for democratic participation.

What then is our path forward? A centrist approach—one advocating neither extreme—might suggest policies promoting responsible gun ownership while bolstering law enforcement capabilities in ways respectful of civil liberties. Such measures could include comprehensive background checks, mandatory safety training courses for firearm owners, stringent regulations around high-capacity magazines or assault-style weapons not typically used in self-defense scenarios—all aimed at reducing risks without infringing unduly upon constitutional rights.

Moreover, fostering dialogue between opposing sides remains crucial if we are ever to bridge ideological divides over this issue. Understanding each other’s fears and aspirations can pave way towards crafting solutions reflecting shared values rather than exacerbating polarizations.

The monopoly on violence principle underscores an enduring challenge within political organization: ensuring societal stability through centralized authority while respecting individuals’ rights and dignity—a delicate balance indeed but one worth striving for in pursuit of just governance amidst diverse interests.

Leave a Reply